11

June

Newly published research explores the impact of antibiotic prescription reviews

By Mary Magnuson

Nursing homes care for more than 4 million Americans each year, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. Considering the residents’ vulnerable health, signs of infection need to be addressed swiftly before they can progress too far.

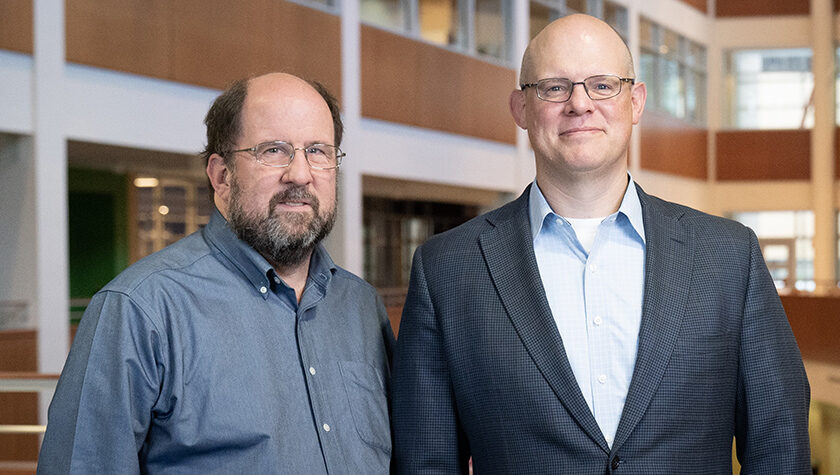

But that quick action can lead to unnecessary or incorrect antibiotic use, often prescribed before test results are in, putting patients’ health at risk and stoking the potential for resistance. A team of researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison — led by Chris Crnich, associate professor in the UW Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Disease — received a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to study antibiotic interventions in nursing homes designed to improve prescribing.

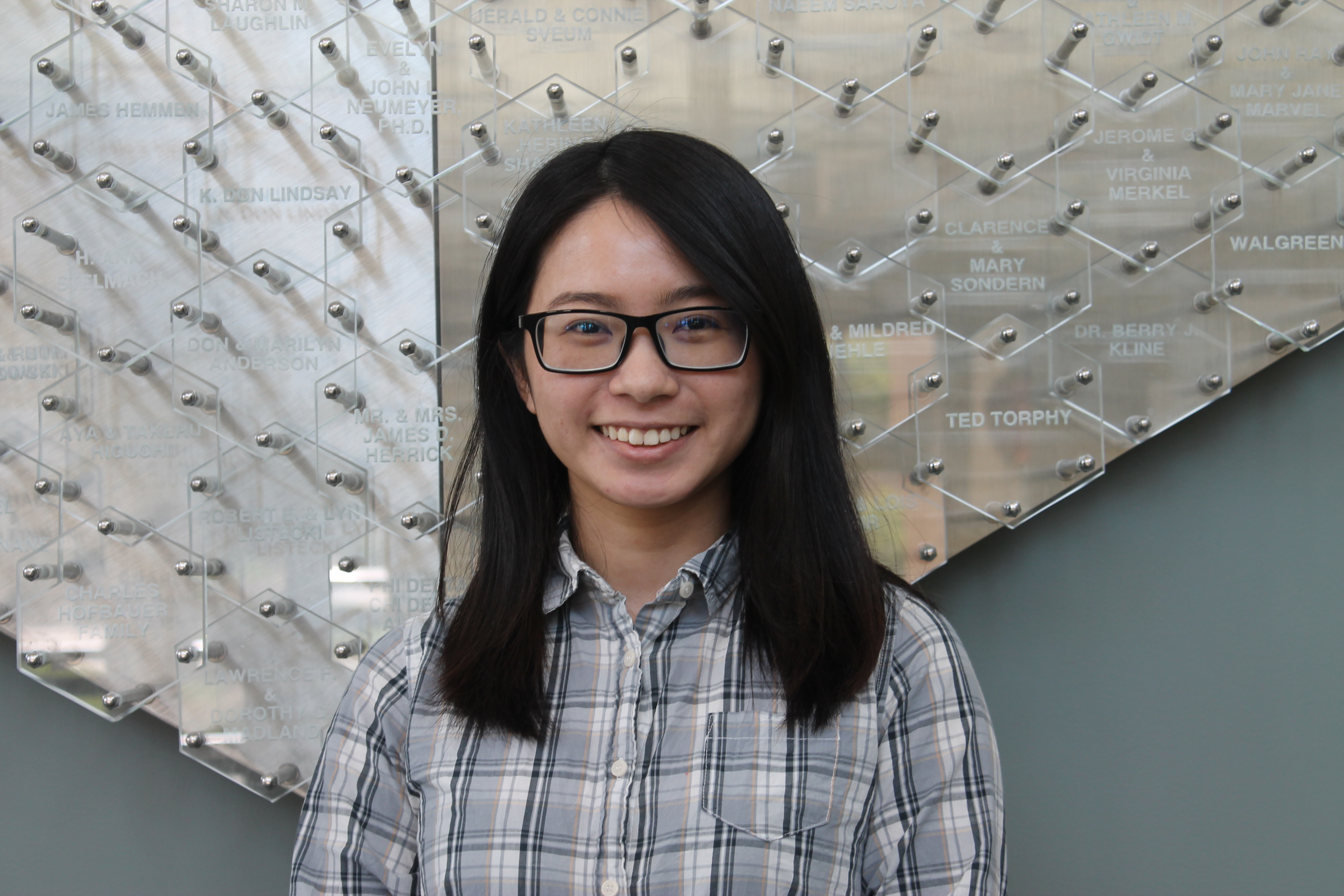

“The overuse and misuse of antibiotics in nursing homes is a serious problem,” says Chi-Yin Liao, graduate student in the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy’s Health Services Research in Pharmacy program. Studies have shown that up to 75 percent of antibiotic prescriptions in nursing homes are not appropriately prescribed.

“It’s causing unnecessary, adverse effects,” says Liao, which includes a heightened risk of medication interactions, allergic reactions, and Clostridium difficile. “In the long run, inappropriate antibiotic use may cause the spread of multi-drug-resistant pathogens.”

“We need to understand what kinds of interventions might help reduce the inappropriate use of antibiotics through evaluating the effect of antibiotic stewardship.”

—Chi-Yin Liao

With Crnich; Jay Ford, assistant professor in the School’s Social and Administrative Sciences Division; and David Nace, associate professor of medicine from the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Liao studied 11 nursing homes in two areas: Madison, Wisconsin and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

In six of the nursing homes, the team tested the efficacy of OASIS (Optimizing Antibiotic Stewardship in Skilled Nursing Facilities), a system redesign that helps facilities integrate alternatives to antibiotic treatments. The other five nursing homes served as a control in the study.

Their research, published in the journal Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology and presented at IDWeek 2019, yielded some surprising results.

The method

With the OASIS interventions, the team employed an external health care “coach,” a trained nurse practitioner, who helped facility staff utilize an antibiotic timeout process to review their antibiotic use 48 to 72 hours after prescriptions were filled to determine whether they could substitute a different treatment, shorten the treatment period, or lower the dose. The reviews examined both antibiotic treatments that had already begun as well as plans for treatments going forward.

Ford says OASIS also stresses an active monitoring approach, which includes closely observing a patient and exploring the effectiveness of alternative treatments before prescribing an antibiotic.

“Most other studies look at the use of antibiotics, but instead, our study looks at the practice of modifying prescriptions,” says Liao. “We need to understand what kinds of interventions might help reduce the inappropriate use of antibiotics through evaluating the effect of antibiotic stewardship.”

What they found

The researchers expected OASIS to have a significant impact on the number of antibiotic change events, or the number of times the facility changed how they administered an antibiotic. But overall, that wasn’t the case.

Although they did not see a big difference in the proportion of antibiotic changes, some modifications were more common among the OASIS group. Liao says that many of the facilities prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotics — antibiotics that can treat a wide range of infections — but with OASIS, they ended the treatment period earlier, after maybe two or three days. Liao says this makes sense because when they can shorten the period of time a patient uses an antibiotic, they can lower the risk of an antibiotic-resistant infection developing in the patient.

While broad-spectrum antibiotics can treat a lot of different infections, Liao says, they’re also more likely to cause antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

“In the long run, this practice will select for the pathogen that is drug-resistant,” Liao says. “Continuing to use broad-spectrum antibiotics will cause the spread of a resistant pathogen.”

The nursing homes using OASIS also changed the class of the antibiotic prescribed less often than in the control group, a result that surprised Liao and the team. Liao said this could be because they prescribed more of the broad-spectrum antibiotics and therefore didn’t have to change the class.

“A lot of the broad-spectrum antibiotic orders were stopped two or three days after they were prescribed,” Liao said. “And this happened frequently in the intervention facilities, but it didn’t seem to change much in the control facilities.”

What’s next

Although antibiotic resistance has become an increasingly common and difficult issue in nursing homes, most research about antibiotic use centers on hospital settings, says Liao.

Studies have also shown that there’s a greater likelihood of antibiotic-resistant infections spreading among nursing home staff and other residents, compared to other facilities, like hospitals. Plus, since residents might go back and forth between their nursing home and the hospital, an antibiotic-resistant infection can be easily spread.

Ford says that he and Liao are working to understand antibiotic use in assisted living facilities as another potential research avenue. Assisted living facilities and nursing homes offer similar services, but nursing home settings are clinical, while assisted living settings are more social and home-like.

“If there are significant issues in those facilities, then there might be opportunities down the road for a similar intervention to take place,” Ford says.

Now, Ford says he and the team, with a grant from the Wisconsin Partnership Program led by Crnich, have started working on a study to implement a urinary tract infection (UTI) toolkit to reduce the use of antibiotics in treating UTIs in nursing homes — another effort to curb resistance.

Ford said nationwide, there’s been a push to start studying settings beyond hospitals for antibiotic resistance, so their studies contribute to this growing body of research.

“There are a couple of studies focusing on antibiotic timeout interventions that are done in the hospital setting, but we don’t we don’t have many studies that have been done on the nursing home setting,” Liao said. “The nursing home is a more resource-limited setting, so some of the types of antibiotic stewardship programs that work in a hospital setting may not necessarily work in a nursing home setting.” The findings from OASIS offer guidance for nursing homes to further exploring the impact of antibiotic timeout interventions to improve overall antibiotic prescribing.