A leader in psychiatric pharmacy, alumna Julie Thiel is an advocate for lifelong learning and human trafficking awareness

By Katie Ginder-Vogel

The Winnebago Mental Health Institute in Oshkosh, Wis., houses 200 patients — including adults and children as young as 6 — and the adjoined Wisconsin Resource Center (WRC) serves 400 patients, who are in the correctional system and come to the facility for mental health evaluations and treatment.

Psychiatric pharmacist Julie Thiel (BS ’98) oversees the medication-related aspects of their care, as the Winnebago Mental Health Institute/WRC pharmacy director and lab supervisor for the State of Wisconsin Department of Health Services (DHS).

Each facility has a medical director, nursing director, and facility director, and the pharmacy provides cohesive services to both DHS facilities.

“The pharmacist is the bridge between psychiatrists and medical clinic doctors,” says Thiel, a graduate of the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy. “Psychiatrists handle mental health needs, the medical clinic doctors handle health concerns that aren’t psychiatric, and pharmacy bridges both. We’re the ones able to make recommendations, catch interactions, and make sure one set of doctors isn’t contradicting another set of doctors.”

“The themes in my career are lifelong learning, saying yes to opportunities when they come up, and when opportunities do come up, being willing to ask others for help.”

—Julie Thiel

On top of her professional work, she has also been volunteering with 5-Stones in Appleton for the past four years, first drawn to the organization after attending a presentation about human trafficking. Through her volunteer work at 5-Stones, Thiel gives educational presentations to middle and high school students, as well as to parent groups, educators, and others — even pharmacists — about how to prevent and recognize human trafficking.

“As pharmacists, we can make that link between trauma and mental health,” Thiel says.

Eighty percent of human trafficking victims seek medical care and, as the most frequently visited healthcare providers, pharmacists are well-positioned to spot red flags and provide trauma-informed care.

For Thiel, raising awareness about human trafficking falls perfectly in line with her career-long commitment to both furthering education and understanding the relationship between mental and physical health.

Homing in on psychiatric care

After graduating from the School of Pharmacy, Thiel began her career as a community pharmacist at Shopko in the Fox Cities, and then moved with her husband to San Francisco for several years. She interned for Kaiser Permanente while she was awaiting her California pharmacist license, and then went to work for Walgreens.

Thiel was placed at Walgreens’ HIV specialty pharmacy, which was also the district’s training store. As an HIV specialty pharmacist, Thiel also got more familiar with the business side of pharmacy — how to do payroll, manage inventory, schedule staff, and deal with billing for specialty drugs.

“I discovered I enjoyed having a specialty,” Thiel says.

Around the same time, Thiel became a yoga instructor and started paying close attention to the link between physical and mental health, wellness and well-being.

When Thiel and her husband returned to Wisconsin, Thiel continued working at Walgreens in a management role, then joined the DHS 12 years ago as a clinical pharmacist in the pharmacy that she now oversees. In that role, she began learning about psychiatric medications and practice and was invigorated by the challenge and the opportunity to affect many facets of patients’ lives.

But there is a learning curve in psychiatric pharmacy, Thiel says, including a safety component that pharmacists on the correctional side need to keep in mind.

“For example, we don’t usually send things in a glass container,” she says. “Nurses squeeze creams into cups because metal tubes could be an issue. We’re always problem solving, trying to figure out what will work well for nurses and patients, with no unintended consequences.”

She joined the College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists soon after arriving at the DHS and served on their annual meeting planning committee, with a focus on the student committee.

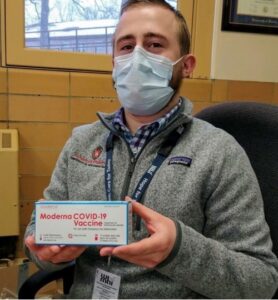

Thiel took over the pharmacy director role with the DHS in 2014, and shortly after she completed her PharmD, which she’d been pursuing virtually while balancing full-time work. As director, she manages a team and oversees quality improvements, influenza vaccines, and now the COVID-19 vaccine programs that serve the WRC and Winnebago Mental Health Institute. Thiel also handles the pharmacy’s USP 800 policies, which includes practices and quality standards for the handling of hazardous drugs to ensure patient safety, worker safety, and environmental protection.

“My day-to-day is always different, and I love the variety,” Thiel says. “The leadership component of my job involves making sure my team operates efficiently, including making sure people are taking care of themselves and aren’t burning out right now because of COVID.”

Thiel’s team of psychiatric pharmacists works closely with nurses and psychiatrists to answer questions about drugs and drug interactions and to provide medications for patients’ return home.

“Our team can talk to either side, psychiatrists and internists, and we have unlimited access to nurses,” Thiel says. “It’s a very interesting job.”

Activating pharmacists against human trafficking

Thiel’s work with 5-Stones and human trafficking prevention is all tied in with her lifelong love of learning and training, Thiel says.

“We meet monthly as a volunteer group. Pre-COVID, I volunteered over 10 hours a month,” she says.

In the fall of 2019, Thiel visited the UW–Madison School of Pharmacy to teach PharmD students how to recognize signs of human trafficking in patients and report it to local law enforcement. In February 2021, Thiel presented virtually to the School of Pharmacy’s Global Health seminar students.

“Pharmacists can have a huge impact on their communities because they can spot things that don’t look right and ask questions.”

—Julie Thiel

“Pharmacists can have a huge impact on their communities because they can spot things that don’t look right and ask questions,” Thiel says.

Some of the red flags she encourages pharmacists to watch for include:

- Isolation (a person is no longer going to school, doing activities, or seeing friends)

- A person physically controlled by an older adult, or is having someone speak on their behalf

- Confusion or lack of awareness of their location or the current date

- Signs of physical abuse or substance abuse

- A person vulnerable to manipulation

If a pharmacist notices some of these signs, they can try to initiate a conversation alone with the patient and to ask more questions: Do they have a debt to someone they can’t pay off? Is someone holding their passport or identification documents? Has someone threatened to hurt them or their family if they leave?

“Drugs of abuse and street trafficking go hand in hand, so our expertise in that area ties in, as well,” she says.

Training the next generation

As a pharmacist for more than 20 years, practicing in multiple states and in various specialties, she has a breadth of experience and a commitment to sharing it. To help pharmacists advance practice, she recently joined the Pharmacy Society of Wisconsin’s Educational Programming Committee and is part of the Request for Proposal subcommittee.

She also established her practice with the DHS as a site for student pharmacists on their Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experience (APPE) rotations, and many students, she says, are surprised when they arrive, expecting a rotation focused solely on mental health.

“They are surprised by how many other conditions people come in with,” Thiel explains. “For example, antipsychotic medication can cause metabolic syndrome. These are complicated patients, in terms of overall health.”

Thiel hired third-year School of Pharmacy PharmD student Aaron Klysen as a pharmacy technician in the summer of 2020 and, impressed by his willingness to take on new projects, expanded his role to include operations and analysis projects as well as patient care.

“We get patients often at their most vulnerable, when therapies have been tried and been unsuccessful,” Klysen says. “In psychiatric pharmacy, you have to do a lot of risk/benefit analyses, and it’s really hard work to figure out what will work, while keeping safety at the forefront.”

Under Thiel’s leadership, Klysen created documentation with photo diagrams to help pharmacy students ease into their clerkship rotations, trained one student, and investigated adverse drug reactions. If a patient was over the maximum recommended dose, he reviewed the clinician documentation and reported it. He also presented to the Drug Diversion Prevention Committee about his research on different containers for patients’ home medications. Klysen’ s largest project was creating a QT prolongation algorithm for pharmacists and prescribers.

“That was the most rewarding — presenting at the medical executive committee, in front of prescribers and clinicians at Winnebago,” says Klysen.

Thiel’s leadership style and the projects with which she entrusted him have opened his eyes to the possibilities of a career in leadership or psychiatric pharmacy. But it’s all part of one of Thiel’s core priorities: enabling education and advancement.

“The themes in my career are lifelong learning, saying yes to opportunities when they come up, and when opportunities do come up, being willing to ask others for help,” she says.