World War II pushed the Apinis family to leave Europe, but the careers they rebuilt in Madison continue to influence student pharmacists and researchers

By Hanzhu Tang

When World War II tightened its hold on Western Europe, Janis and Anna Apinis, their young son, John, and even younger daughter, Rasma, relocated to the United States as refugees, leaving everything behind, including promising pharmacy careers.

Their decision to leave Latvia, their home country, transformed their lives and careers, and continues to impact the lives and careers of many student pharmacists at the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy.

Janis and Anna arrived in Madison with two small kids, two suitcases, and not a word of English or a dollar to their name. Attached to all their coats were baggage tags in English to make sure they got to their destination. That was the starting point.

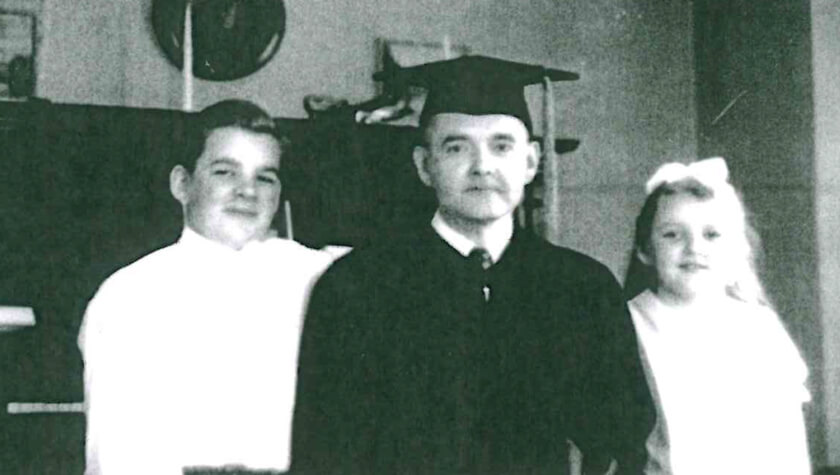

They realized that their Latvian graduate degrees in pharmacy were not accepted here, so they had to find other jobs. In time, Janis enrolled at the UW–Madison School of Pharmacy to continue to pursue his passion. Sixty-five years ago, in 1954, he graduated from the School with his bachelor’s degree in pharmacy.

“My father, now deceased, was very dedicated to the profession of pharmacy,” remembers John. Given his father’s devotion to and passion for pharmacy, John created several scholarships to support student pharmacists at the School: the Apinis Memorial Great People Scholarships, which support two PharmD students each semester in honor of each of his parents, and the John Janis Apinis Scholarship, which supports one per semester. He also created the Janis Apinis Professorship, which supports a faculty member in the School’s Pharmaceutical Science Division.

“My father’s passion was health care and helping people, so I want to help students in hopes that they will go out into the world and help individual people,” says John. “These scholarships and professorship are a fitting living memorial in my father’s name.”

Rebuilding

The story of the Apinis family begins in Latvia in the 1930s, where Janis and Anna both earned master’s degrees in pharmacy. Before World War II, Janis had climbed the ladder to become the director of the national drug manufacturing enterprise, but the family later decided to strike out on their own and bought a small country drug store, where Janis and Anna worked together.

“That is when the first Russian invasion occurred,” John says. “We survived that. Then came the German invasion. We survived that, too, but when the Russians were coming back for the second time, we had to leave since we would have been then deported to Siberia, where most people perished.”

When John was 4 years old, he and his family left Latvia, and ended up in the American Zone in Germany, where they saw the end of the war. They spent the next five years in various refugee camps before the opportunity came to emigrate from Germany to America. There was always the fear the Red Army would move again, and the United States was seen as the safest place on earth.

“I still can remember the bombing and the artillery barrages, all of which we survived,” recalls John.

After the war, Europe was awash with displaced persons that could no longer go home, and a number of countries, including the United States, agreed to accept some of the refugees. To be granted entry to the United States, refugees had to secure a sponsor that would arrange a place to live and provide a job.

Fortunately, given his experience, Janis received two resettlement offers, one located in Madison and one in Seattle. He chose Madison, and the family’s sponsor, Luther Memorial Church, arranged work for him at the Madison Drug Company warehouse, as well as a house that could be rented inexpensively. The company was a drug wholesaler and distributor. Anna found a job cleaning private homes, and later, an entire floor in a large office building.

“They were happy just to have jobs and to be in America. Our house was the only one on our block that flew the American flag on national holidays,” says John.

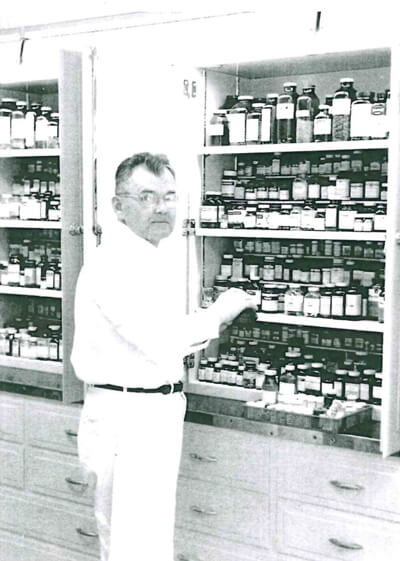

To work as a pharmacist again, Janis realized he needed a degree from an institution in the United States, and after a few years he enrolled at the UW–Madison School of Pharmacy, while continuing to work. After graduating, he spent the rest of his career as a pharmacist at the Madison General Hospital. One of his favorite aspects of that job was serving as a mentor to the new pharmacists.

John vividly remembers the quiet focus and dedication of his father. “He never looked at the clock,” he says. “If it was 5:00 pm but there was still some work to finish up in the pharmacy, he would stay until it is done. He would spend a lot of time at the pharmacy because it was important to him to do it right. For many years he went to work on a city bus, or a bicycle.”

Anna, too, was pulled back to health care and she learned to be a medical technician with on-the-job training while working in the laboratory of Frederic Mohs — a researcher and surgeon with the University of Wisconsin Hospital, known for developing Mohs micrographic surgery.

“Dr. Mohs pioneered a technique for treating skin cancer, currently in wide use, and my mother was in his laboratory, making the microscope slides for him to review,” says John. “She was sent later to other hospitals to train their technicians on the laboratory process.”

After all the obstacles, the Apinis’ thrived in the U.S., and their children — John and his sister, Rasma — both earned PhD degrees from Big Ten universities: John in electrical engineering and his sister in pharmacy, who recently retired as a full professor of pharmacy.

Janis and Anna continued to live in their original Madison home until Janis passed away.

Continuing the legacy

Through the three scholarships and the professorship at the School, John and his family hope to continue to transform lives by advancing pharmacy education and pharmaceutical research.

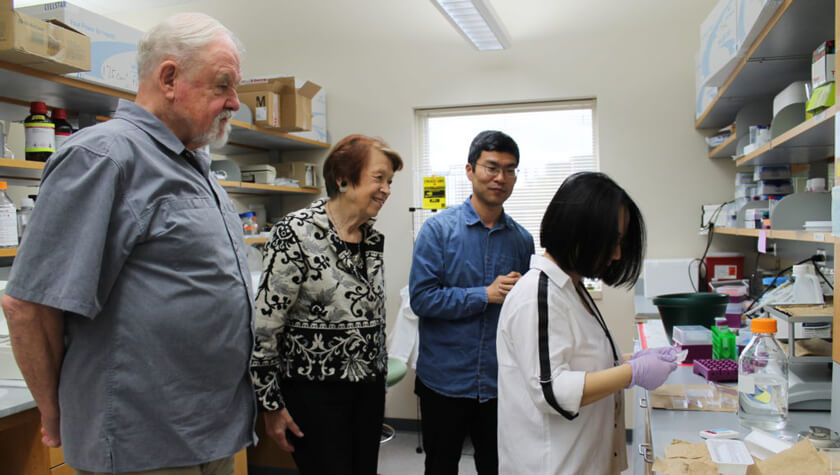

Most recently, the Apinis scholarships went to PharmD students Garrett Gunderson, Maria Huck, and Sydney Ertz. Professor Weiping Tang currently holds the five-year professorship.

Tang is using the support to develop small molecules, called PROTACs, to degrade disease-causing proteins. These PROTACs have the potential to become novel therapeutics to treat diseases that are not currently treatable with medication.

“In the past, we used genetic methods to remove these proteins. But now using this strategy, we can degrade or get rid of the protein that is much more convenient and much faster than the genetic tools,” says Tang. “PROTACs have essentially changed the paradigm of drug discovery.”

Through the professorship, Tang is able to put more resources into this area of research, such as adding researchers to the Tang Lab and advancing platforms to collaborate with other researchers on campus.

John finds Tang’s research impressive. “What he’s pursuing has tremendous potential and has broad applicability,” he says. “It is a very robust approach to cure various illnesses and diseases.”

Before Tang, Professor Lingjun Li held the professorship, using the support to strive for earlier detection and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease through identifying biomarkers.

The effect of the Apinis’ support is just as strong for student pharmacists, who are pursuing the same goal of helping people that motivated Janis more than six decades ago.

“The Janis Apinis Great People Scholarship gave me the opportunity to focus on my academics and explore the many different pathways in the field of pharmacy,” says Denise Garner, a PharmD student who received the scholarship in 2018. “I am forever grateful to the Apinis family for helping me move closer to my dreams and goals.”

Read more about Professor Weiping Tang’s research and his lab, and his recent Vilas Mid-Career Investigator Award.