Alumna has spent her career propelling neuroengineering and neurotechnology

By Katie Ginder-Vogel

“Early on, I realized I wanted to do science to help people,” says Tracy Laabs (BS ’01). “I’ve always been a rabid consumer of information, while thinking critically. I like to read a lot, learn a lot, and put it together for myself.”

This fire for research is what pulled her into the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy’s Pharmacology and Toxicology program and what propelled her professional success after her graduation. Laabs — who is now the chief development officer at the Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroengineering in Geneva, Switzerland — has extensive research experience, covering neuroscience, neurotechnology, molecular biology, physiology, human performance, and regenerative medicine.

For all she’s accomplished, the School of Pharmacy has selected her as the 2020 PharmTox Alumnus of the Year.

“I am really honored and really happy they recognized me,” says Laabs. “I feel like it’s a validation of the importance of pursuing a career that’s not necessarily traditional but still impactful.”

The majority of Laabs’ career hasn’t been doing typical bench work. Instead, she’s helped fuel cutting-edge neurological research, including technology to modulate the brain to treat mental health conditions and a subcutaneous device to monitor epilepsy.

“One of my biggest passions is bringing people together to drive science forward.”

—Tracy Laabs

“Dr. Laabs exemplifies the Wisconsin Idea —that she’s taken the education she began at the School of Pharmacy and directly improved lives and research beyond the boundaries of the classroom,” says Jeff Johnson, Pharmacology and Toxicology program director. “Her career has had a global impact.”

Love for human physiology

Originally from Green Bay, Laabs grew up in Springfield, Ill., and was always interested in science.

As an undergraduate at UW–Madison, she was a pharmacy technician at Walgreens. In her third year on campus, she enrolled in the Doctor of Pharmacy program at the School of Pharmacy. But soon after, she switched to the Pharmacology and Toxicology program so she could focus on research.

“I quickly learned that I love hard-core pharmaceutical sciences,” Laabs says. “Human physiology was one of my favorite courses. Drugs are fascinating, especially the ones that affect your brain.”

As an undergraduate and for several years after earning her bachelor’s degree in Pharmacology and Toxicology, Laabs worked in the lab of Professor Warren Heideman, who retired after 30 years in February 2020, in the School’s Pharmaceutical Sciences Division. In the Heideman Lab, she researched the yeast cell cycle.

“Dr. Heideman was instrumental in setting the foundation for my whole research career,” says Laabs. “He was my first mentor and a fantastic professor and friend.”

Delving into neuroscience

After graduating from the School, she entered the National Institutes of Health Oxford-Cambridge Scholars program at the University of Cambridge in England, which was focused on the molecular underpinnings of central nervous system regeneration.

During her PhD program, Laabs studied spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, and nervous system injuries from a molecular standpoint. Laabs said the graduate-level courses she took as a PharmTox major helped her in graduate school.

“At Cambridge, I audited neuroscience classes because my undergraduate degree focused on pharmacology, but the fact that I had taken other graduate-level classes really helped in my PhD program,” says Laabs. “I had contributed to a paper in the Heideman Lab, which helped me to understand the publication process, and the program’s opportunities to set up experiments and think critically set the foundation for a solid research career.”

During graduate school, Laabs published a paper in the Journal of Neuroscience as the first author. She also contributed to other publications and wrote a review paper.

Laabs spent half of her PhD program in Cambridge and half at the NIH in Washington, D.C. As she was considering her choices for postdoctoral research, a teammate on her intramural soccer team in Washington, D.C. happened to mention that her company was hiring neuroscientists.

Laabs was hired to join Strategic Analysis Incorporated, a contractor for the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the U.S. Department of Defense’s innovation engine, in 2008. She learned an important lesson from that job search.

“Don’t be afraid to take a non-traditional career path,” she says. “Network in creative ways; don’t be afraid to leverage your soccer team for job opportunities.”

Innovation at DARPA

Laabs’ role at Strategic Analysis Incorporated involved providing technical expertise and scientific program management support for programs at DARPA in the Defense Sciences and Biological Technologies offices. Laabs was on-site at DARPA for most of her time with Strategic Analysis Incorporated, working with academic, government, and industrial labs to drive innovation in neuroscience and neurotechnology.

“They have a huge investment in biomedical engineering and biotechnology,” says Laabs. “I always wanted a job where I did something new every day and could learn about many different things, and it was a really fascinating job.”

The projects Laabs worked on aimed to develop a better understanding of how the brain and physiological systems react to stress. The goal was to develop strategies and technologies to combat and even prevent stress-related conditions. One project even aimed to develop neural interface systems that could eventually modulate the brain to treat depression and anxiety in veterans.

“I loved working as a contractor at DARPA, and after seven years, I was ready for a new challenge,” Laabs says.

On a phone call with Professor John Donoghue, a pioneer of brain-computer interface research and founding director of the Brown Institute of Brain Science at Brown University, Laabs learned about a new institute Donoghue was helping to found — a nonprofit foundation to pursue high-risk research in neuroscience and neurotechnology.

“He said he was looking for an assistant director,” says Laabs. “It was similar to what I did at DARPA, but to start a whole new entity. It was an opportunity I couldn’t pass up.”

Wyss Center advances in neuroengineering

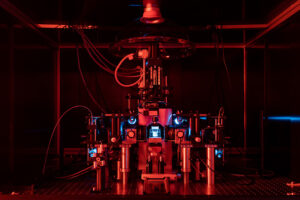

Laabs became the founding deputy director of the Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroengineering, established in 2014 by the Swiss philanthropist and entrepreneur Hansjörg Wyss. Laabs’ first five years at the Center involved setting up lab infrastructure and building a team of interdisciplinary experts in neuroengineering. Laabs explains that there is a gap in neurotechnology between academic prototypes and human trials, so part of the Wyss Center’s role is to work with professors and regulatory authorities to bridge this gap in the field of medical devices.

“We were more of a funding agency, initially,” she says. “We didn’t have our own R&D staff yet, so we reached out to the scientific community and used philanthropic funds to augment their capabilities and build our own.”

Laabs was recently named Wyss’ chief development officer, in charge of the center’s strategy, partnerships, and fund development efforts to accelerate the translation of science and technology to patients.

“One of my biggest passions is bringing people together to drive science forward, so this is a perfect role for me,” Laabs says. “In the last five years, we’ve set up interesting engineering projects and started to develop fascinating technology, so now we can partner with more scientists to research and test it to understand the human brain better.”

The Wyss Center has many academic and clinical collaborations in Switzerland, and Laabs’ new role aims to expand collaborations to try to get clinical partners in the U.S. and extend the reach of the Center’s technology.

The Wyss Center has many industrial collaborations with neurotechnology companies in the U.S. and Europe, including Blackrock Microsystems in the U.S. and Cortec Neuro in Germany.

“Blackrock Microsystems is one of the only companies to have technology that’s approved for implantation in the human brain for research purposes, to measure the brain at the resolution we need,” says Laabs.

One Wyss Center program focuses on restoring movement and communication in people with paralysis, using neuroscience to understand how the brain encodes movement and engineering to develop technology that can use brain signals to drive movement in people with paralysis. The aim is to then develop control algorithms that could enable someone to move a cursor or a robot arm with their mind.

“I learn about engineering, science, and what can we learn if we have access to the brain in these ways,” says Laabs. “Science is the most important thing we have going for us these days.”

Advice for the next generation

UW–Madison’s campus closure, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, prevented Laabs from making it back to campus for the PharmTox graduation event, where she was supposed to receive her award and deliver an address to the PharmTox Class of 2020.

“I’m actually a little devastated that I can’t come back,” she admits. “I still have so many good friends there. I miss the hot and spicy cheese bread at the Farmer’s Market.”

Despite being unable to impart it in person, Laabs still has advice for UW–Madison students.

“Hard work opens many doors, and it also helps to be open-minded and to think about how to use your strengths from your undergraduate program in different and interesting ways,” she says. “Don’t be afraid to try something new.”