Graduate student Taylor Watterson uses wearable technology to measure and address occupational fatigue in pharmacy

By Arushi Gupta

As an intern at a chain pharmacy in Pennsylvania, Taylor Watterson (MS ’18) had the chance to float between pharmacy locations and get advice from the pharmacists who worked in them. As a pharmacy student, what she heard was troubling: Some of the pharmacists she spoke with were unhappy at their jobs.

Instead of deterring her from following her interest in pharmacy, it pushed her to root out and address issues in the profession. After earning her PharmD, she enrolled in the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy’s Health Services Research in Pharmacy PhD program and began to dig into occupational fatigue in pharmacists.

Occupational fatigue sets in when a heavy workload prevents pharmacists — or any professional — from working at their normal capacity, and it can include a number of physical and mental components. The problem of occupational fatigue in the pharmacy profession has not received much attention from researchers. Unlike for other health care professionals, like nurses and physicians, there is currently no literature addressing occupational fatigue in pharmacists.

“We’re not only helping our students as future pharmacists, but we’re also helping their mentors, their bosses, and their preceptors work at the top of their capabilities and improving their well-being.”

—Taylor Watterson

Through a 2019 grant from the Midwest Center for Occupational Health and Safety (MCOHS), Watterson became one of the first researchers to address pharmacist fatigue. So far, she’s launched several surveys and implemented wearable tech in her mission to excavate the parameters of pharmacists’ capacity, and when a few long days blur into a chronic problem.

Identifying fatigue

“Fatigue could mean any number of things. It could be backaches from standing for 12 to 14 hours on their normal shifts, not having a lunch break, or not getting a good night’s sleep because they work a 14-hour shift, go home and then come back and work another 14-hour shift,” says Watterson.

A key issue, she says, lies in establishing criteria or a definition to recognize at what point pharmacists experience occupational fatigue.

“How do we know pharmacists are fatigued? That’s a struggle,” says Watterson.

Watterson is using a multi-pronged approach to answer that question, which will enable future research into the prevalence of and risk factors for fatigue among pharmacists in various practice settings. One of her early steps included creating a survey instrument to capture information about whether our pharmacists are fatigued and to what extent. Then, she deployed wearable devices.

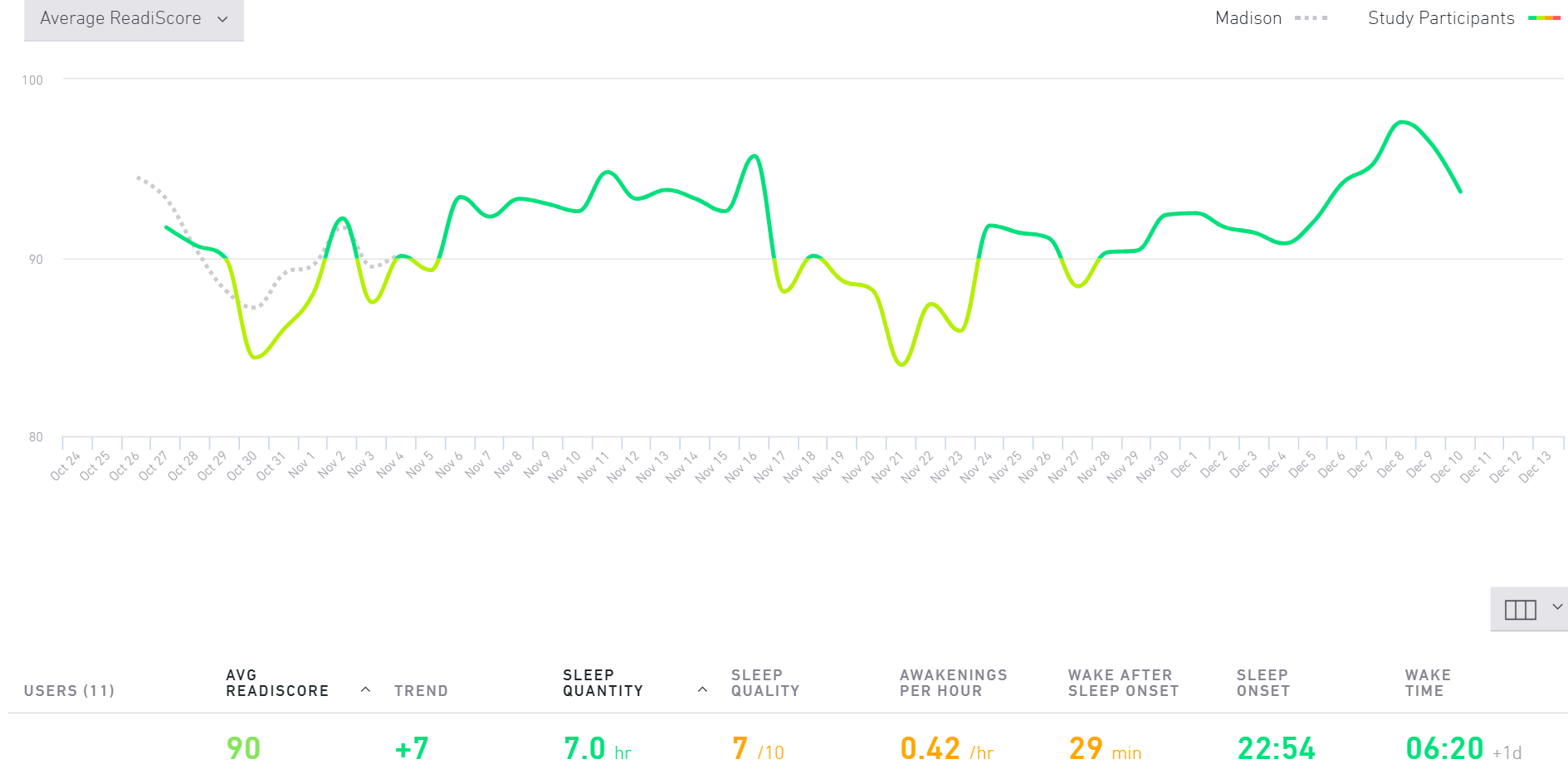

Through the MCOSH grant, Watterson launched a study using Readibands, developed by the U.S. Military, to track pharmacists’ wrist movements and time of day. The pilot study included 60 pharmacists, tracked for a 14-day period.

To correlate the Readiband data with measures of fatigue, the pharmacists also took the survey developed by Watterson, as well as a burnout questionnaire.

“Using these tools, employers can understand whether pharmacists are fatigued and relay a new intervention, such as switching over job tasks to a qualified technician, and they can monitor how pharmacists are doing,” says Watterson. “If you’re asking someone to work in these trying conditions where they feel like they’re not able to perform at their best, that can increase the risk of them leaving their jobs.”

Many of the participants in Watterson’s study are in rural areas, where pharmacists are often the most accessible health practitioner for miles around. In these environments, pharmacists are more likely to take on additional roles and offer a wide array of services, increasing the possibility of fatigue.

“We thought long and hard about the Wisconsin Idea and giving back to the community,” says Watterson. “Since Wisconsin has many rural areas, fatigue in rural pharmacists could have different implications, and we are giving special emphasis to them.”

The burden of fatigue

In her conversations with pharmacists, Watterson says many of them shared that they were working on adrenaline. Because of this high-adrenaline state, they might not know they are fatigued until the end of their 10- to 15-hour shift when they realize, for example, that they didn’t get a lunch break.

The Readibands can help measure and verify pharmacists’ work hours, but the implications on job performance and satisfaction need to be assessed separately. Apart from pharmacists’ health and well-being, this also raises the question of patient safety as well.

Through a survey she distributed at a meeting of the Pharmacy Society of Wisconsin, Watterson learned that pharmacists might not be aware of how fatigue can contribute to short cuts or lapses, which could pose a risk to patients.

“I think it’s an important conversation to have,” she says. “What are we asking our pharmacists to do? Are these realistic expectations?”

Community pharmacists are in unique and complex work environments, at the intersection of patient care and business.

As pharmacists expand their scope of practice — such as by providing immunizations and offering comprehensive medication reviews — they can allocate some duties to qualified interns or technicians. But the responsibilities that pharmacists most often cite as fatigue-inducing aren’t related to their evolving duties; instead, it’s business administration duties that bog them down.

“Pharmacists love counselling, talking with patients, participating in these clinical roles that they’re trained for,” says Watterson. “It’s important for us to see how we can best make that happen, while respecting that in a business model, patient care is just one area of the pharmacist’s work.”

Knowledge is power

As Watterson works through analyzing the physiological and survey data she’s collected from community pharmacists, she’s looking to examine other practice environments for similarities and differences. Next, she wants to expand her study to ambulatory care pharmacists, as well as pharmacy clerks and technicians, especially if they are delegated more tasks as pharmacists pivot to patient care.

Watterson is also considering studying the implementation interventions such as breaks, delegating tasks, and changing sleep patterns to investigate their effectiveness.

This research into occupational fatigue in pharmacists, though still underway, has already led to changes in student pharmacists’ education at the UW–Madison School of Pharmacy: Pharmacist well-being has been incorporated into the PharmD curriculum in two courses, one on pharmacy management and one on medication safety.

“We are having discussions with our students early on so that they can anticipate this potential struggle and arm them with strategies to mitigate fatigue and burnout before it begins.”

—Taylor Watterson

“We are having discussions with our students early on so that they can anticipate this potential struggle and arm them with strategies to mitigate fatigue and burnout before it begins,” says Watterson.

As this area of research gets more attention, the effect will spread through the profession to address common sources of fatigue. With knowledge comes the potential for change.

“We’re not only helping our students as future pharmacists, but we’re also helping their mentors, their bosses, and their preceptors work at the top of their capabilities and improving their well-being,” says Watterson.