School of Pharmacy researchers illuminate and address pharmacists’ barriers to providing naltrexone injections

By Arushi Gupta

Naltrexone injections, which block the effects of opiates on the brain and decrease the desire to abuse certain substances, are a crucial facet of treatment for people with opioid or alcohol misuse disorders. A single injection provides a month of support to patients as they strive to better their lives. But finding a nearby facility prepared to deliver the injections is half the battle.

A recent study by University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy Assistant Professor Kevin Look, of the Social and Administrative Sciences Division, found that 14 of Wisconsin’s counties don’t have a formal substance abuse facility, pushing treatment options out of reach for many. However, his study also found that all but one of the counties without a treatment facility had access to at least one community pharmacy, making them key access points in the fight against addiction.

“If you go to smaller rural communities in Northern Wisconsin, there might not be a physician within an hour’s drive — but there will be a pharmacist,” says Jay Ford, assistant professor in the School’s Social and Administrative Sciences Division.

Wisconsin’s pharmacists are legally empowered to provide long-acting naltrexone injections, but questions remain: How many pharmacies are offering the service? What are their best practices and barriers? How can we get more pharmacies across Wisconsin involved?

Ford set out with Aaron Gilson, health policy research scientist in the School’s Sonderegger Research Center for Improved Medication Outcomes, as well as Professor Dave Mott (BS ’88, MS ’92, PhD ’95), chair of the School’s Social and Administrative Sciences Division, and School of Nursing Professor Gina Bryan, to find answers and develop a guide to help pharmacists navigate the administration of naltrexone injections.

“It’s important to set up a culture in the organization to let pharmacists and staff understand that they’re there to help individuals with an opioid use disorder move forward.”

—Jay Ford

Over the course of six months, the research team sent surveys to about 400 pharmacies in 20 counties that the Wisconsin Department of Health identified as being high-need areas. The team also interviewed pharmacists in these counties who are currently providing naltrexone injections and providers who were working with pharmacists to offer this service. As responses from the pharmacies rolled in, Ford developed examples of naltrexone injection models being used by the pharmacies, identified the barriers pharmacies administering naltrexone injections face, and has started working on how to overcome them.

Understanding barriers

Pharmacists reported that one of the biggest barriers to administering naltrexone is cost. While it is possible to get reimbursed for the cost of the medication, insurance does not typically reimburse pharmacists for their time to provide the injection; however, in some instances, such as drug court clients, the pharmacist may receive a cash co-pay for providing the service. However, this co-pay does not cover the pharmacist’s cost to administer the injection.

“Although pharmacists are typically able to recoup the cost of the actual medication, they’re not currently under reimbursement policies,” says Ford. “Some pharmacists look at it and say, ‘I can’t afford to do this.’”

Other barriers include low awareness of the passage of a Wisconsin law in 2016 that extended pharmacists’ scope of practice to include injectable medications, including naltrexone. Additionally, the injection is administered around the gluteus, so patients require the privacy that not all pharmacies have the space to provide.

Staffing issues are also a concern, according to Ford. Pharmacists are legally empowered to provide the injections, but as it’s new to the scope of practice, they may require additional training. And smaller pharmacies might not have enough staff to allow a pharmacist to step away from their normal workflow to administer an injection.

Disseminating best practices

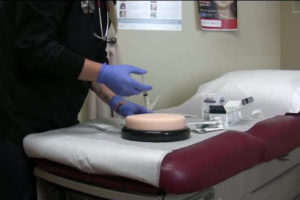

To address these barriers, Ford, Gilson, and other members of the research team are creating a “Best Practices Guide” that highlights equipment and specific steps for pharmacists to launch the naltrexone administration service and access the requisite training, which is available through a partnership between the Pharmacy Society of Wisconsin and the School’s Division of Pharmacy Professional Development.

Administering naltrexone to a patient with opioids in their system could produce a negative reaction, so a rapid drug urine test is a necessary precursor to the injection. Some pharmacies might require a special waiver to be able to conduct such a test, and the guide includes instructions on how to go through that process. Moreover, the guide also offers ideas for ways pharmacies can reach out to other providers in the community and form relationships to get the word out to patients and community members.

In addition to the guide, Ford developed a toolkit — a detailed expansion of the Best Practices Guide that gives some background of the opioid epidemic and the benefits of naltrexone.

“I think this will benefit pharmacies by offering them an opportunity to develop a new service that will help their community,” Ford says.

He is looking forward to conducting more in-depth analyses with pharmacies and is applying for a grant with the National Institute of Drug Abuse to test the effectiveness of the Best Practices Guide and toolkit.

Improving our communities

“One of the pharmacists I interviewed said that for pharmacists who are offering this service, it’s really important to create a no-judgement zone,” says Ford.

For example, some pharmacists, such as John Lemke (PharmD’ 15) and Jeff Kirchner (BS ’88) at Streu’s Pharmacy in Green Bay, are creating naltrexone delivery services in conjunction with the criminal justice system to help recently released inmates continue to access substance abuse treatment, which they’ve often started while incarcerated.

“It’s important to set up a culture in the organization to let pharmacists and staff understand that they’re there to help individuals with an opioid use disorder move forward,” says Ford.

“I think this will benefit pharmacies by offering them an opportunity to develop a new service that will help their community.”

—Jay Ford

Ford recounts his interview with a pharmacist who said individuals struggling with opioid use disorder cannot will their addiction away any more than a patient with high blood pressure who can will their blood pressure to go down.

“It’s a diagnosis, and it does require medical intervention,” says Ford.

He is hopeful that his research will help patients connect with a pharmacy and find a regular place that they can go approximately every 30 days to get their naltrexone injection, which would keep them on the path to sobriety and improve their overall health.

“I think the Wisconsin Department of Health is excited by the idea of pharmacists helping suppress the opioid crisis,” says Ford. “We’re continuing to talk to them about new and innovative ideas that we could test out in the upcoming year.”