School of Pharmacy team conducts statewide testing to facilitate patient education

By Mary Magnuson

Patients look to pharmacists as educators about opioid medications. But, although pharmacists have the expertise to fill that role, many don’t feel like they’re equipped to start the conversation, says Tanvee Thakur (PhD ’20).

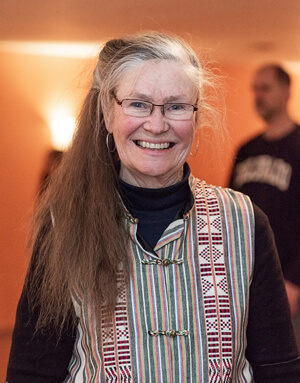

Thakur, then a graduate student in the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy’s Health Services Research in Pharmacy program, uncovered this sentiment through research conducted with Professor Betty Chewning, of the School’s Social and Administrative Sciences Division. Furthermore, her research found that because pharmacists were hesitant to start the conversation, many patients ended up not even knowing that their pain medication was an opioid.

“It’s a sensitive topic because there is so much stigma around opioid use in general, but it’s also an important topic because opioids are prescribed frequently and they carry real risks that patients need and want to understand,” says Thakur.

The opioid epidemic, according to the Centers for Disease Control, marks one of the leading causes of injury-related deaths in the United States. Over 67,000 people died from drug overdose in 2018, and 70 percent of those deaths had to do with opioids, many of them prescription.

“As pharmacists are already educating patients on medication, our handout can help facilitate and enhance those conversations.”

—Tanvee Thakur

With help from Chewning and Tara Airola (PharmD ’20), and support through a grant from the Community Pharmacy Foundation (CPF), Thakur is creating a simple handout to help facilitate the conversation and improve patient education.

The handout contains information on what opioids are, how they can be useful, as well as how to take them safely, monitor pain, store them, dispose of them, and other helpful information.

“As pharmacists are already educating patients on medication, our handout can help facilitate and enhance those conversations,” says Thakur.

Developing the handout

The pharmacist’s role in the opioid prescription process is paramount, Chewning says, because pharmacists are the last people speaking with a patient before they receive the medication. And most prescribers count on pharmacists talking with about opioids with patients, so it’s important for pharmacists to feel confident in communicating about the risks.

Thakur developed the handout after doing research with an existing handout created by UW Health. In previous research, Thakur interviewed several patients with active opioid prescriptions, both long term and short term, and asked them how they liked the handout, and whether they found its information useful. With this data as a foundation, Thakur created her own handout.

After initial testing and feedback through interviews with pharmacists, the team used funding from the CPF grant to revise the handout and send it out to a wider sample of 700 pharmacists across Wisconsin to gather feedback. They asked pharmacists whether they would use it in their consultations and what they would change about it. In this stage, the survey went to randomly sampled pharmacists taken from a mailing list provided by the WI Department of Safety and Professional Services. Then, they began testing the handout in real patient consultations in community pharmacies, while Airola observed the consultations and took notes.

“Basically, we tried to develop and refine a handout and understand the suitability and acceptability of the use of this handout in a community pharmacy,” Thakur says. “And it was an iterative process where the handout was continuously revised and retested and updated.”

Throughout their testing, Thakur says many of the pharmacists they’d worked with had found the handout helpful and planned to continue using it, even though Thakur hadn’t yet finalized the content.

Thakur says one of the most interesting parts of the testing process was hearing myriad perspectives and opinions on what should be included on the handout. Pharmacists are passionate about educating their patients and helping them through different processes, she says, so the team received a lot of support along the way.

With the CFP grant funding, the team completed their testing and finalized the handout, and the grant will also help them disseminate the handout on a wider scale. Thakur says it will go up on the CPF website in June 2020, and CPF will also send it out to their members, so pharmacists across the country will be able to use the handout in their own patient consultations.

School of Pharmacy connections

To some extent, Chewning says, the project started in the classroom. A lot of their ideas for the grant came from student feedback in Chewning’s communications lab, a required course for third-year PharmD students, which Thakur helped teach. While studying consultations, the students helped them refine the handout in its early stages.

Many of the pharmacists they worked with to get feedback on the handout were School of Pharmacy alumni who had also been through the communications lab.

“There’s a sense of loyalty among graduates of this program,” Chewning says. “It’s always moving for me, both as a researcher but as someone who has this connection, to see it repaid so deeply. Our alumni are extremely gracious.”

Thakur says the project has helped her refine her career goals — she said opioid education is an interesting topic and one she’d like to continue working on in the future, if possible.

“This has helped me establish myself as an independent researcher and find a stream of research that I really feel passionate about and helped me see what aspects of patient care I can contribute more to,” says Thakur.